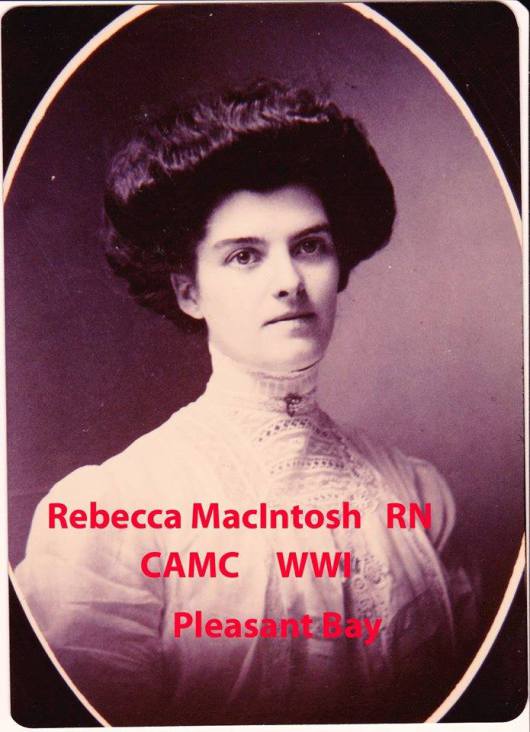

Rebecca MacIntosh was born on 29th June 1892 in Pleasant Bay, Inverness County, Nova Scotia.

We know that Rebecca’s Grandfather James MacIntosh, was a pioneer and one of the first settlers who came to Nova Scotia in the early 1800’s. I found an extract in a book called ‘The History of Pleasant Bay’. There is an extract from it to be found by scrolling further down this page. It includes references to the McIntosh family.

The 1901 Census for Canada on Ancestry.co.uk reveals that the MacIntosh family was living in number 8 Dwelling House, Pleasant Bay, Inverness County, Nova Scotia. Head of the household was Peter O. MacIntosh aged 55 who was a Farmer. He was born on the 15th June 1845 in Nova Scotia and was of Scottish heritage. His wife Christy was 45 years of age. She was born on the 21st November 1853 in Nova Scotia. Their listed children were John P. aged 14 who was born on the 23rd April 1886. Margaret 13 was born on the 30th March 1888. Rebecca was 9. Cassie B. was 5 and was born on the 2nd December 1895. Also listed was Annie MacIntosh, (Peter MacIntosh’s mother). She was 83 and had been born on the 30th October 1817 in Scotland. She had emigrated to Canada in 1843.

I cannot find Rebecca on any Census after 1901 although her parents were still living in Pleasant Bay in 1911 with their youngest child Cassie Bell aged 15.

I found the following information about Rebecca on a website called ‘Finding the 47, Nurses of the First World War’ by Debbie Marshall. It is such a good account of Rebecca’s life that I have reproduced it in full here. I hope Debbie Marshall doesn’t mind.

The Death of a Nurse Amidst the Tumult at the End of the War

There is a 90-year-old legend in the North Wales town of Bodelwyddan. On some nights you can hear the sound of soldiers marching through the town, but if you look, none can be seen. The soldiers are the spirits of Canadian troops that rest in St. Margaret’s Churchyard in the town. 208 Canadian soldiers are buried there, most of them victims of the influenza epidemic that was rampant in Europe and North America in early 1919.

One of the “Canadian soldiers” whose ghostly footsteps may still be heard in Bodelwyddan is Nursing Sister Rebecca McIntosh, who died at No. 9 Canadian General Hospital in Kinmel Camp in March 1919.

Rebecca was born on January 29, 1892 into a farming family in Pleasant Bay, Nova Scotia. Her parents were Peter and Christy McIntosh and her family included older siblings Margaret and John, as well as a younger sister named Cassie and an elderly grandmother named Annie. All, with the exception of Annie (who was from Scotland), had been born in Nova Scotia.

Faith seems to have been an important part of Rebecca’s early life. She was a member of St. Matthew’s Presbyterian (now United) Church in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and her brother John (who she names as next of kin in her enlistment papers) was a Presbyterian minister. Many members of St. Matthew’s enlisted during the Great War. Several lost their lives, including M. Pearl Fraser, a fellow nursing sister who was killed in action aboard the HMHS Llandovery Castle. Another notable member of that congregation was Will Bird, the famous WWI soldier and journalist who chronicled his experience of the war in numerous books and articles.

Sometime after graduating from high school, Rebecca attended and graduated from nursing school (although the school she attended is unknown). In 1914, she survived a serious bout of scarlet fever. By 1917, she was well enough to enlist in the CAMC. At the time of her enlistment in April of that year, she was 25 years old, 157 lb. and 5’8 ½”. Her father had died (perhaps he had also been affected by scarlet fever) and her mother was living in Bridgewater, Lunenburg County, likely with her son John.

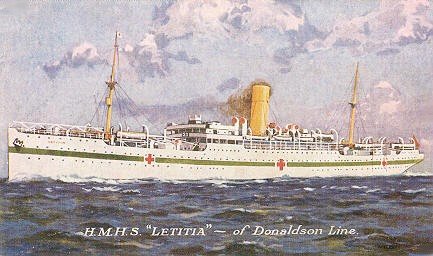

On the 25th of April, Rebecca set sail for England on board the hospital ship HMHS Letitia (a ship that would later run aground and sink on a return journey to Nova Scotia). After arriving in Liverpool a week later, she was assigned to the Kitchener Military Hospital (later known as #10 General) located in a former workhouse in Brighton. It was a comfortable assignment, according to Dr. Charles Thrush, one of the physicians working there–

“We receive only wounded from the front and do not take local casualties. One of my duties is to meet all ambulance trains, inspect unloading, placing in ambulance and sending to hospital. It is very interesting…Brighton is a wonderful place. It is the chief summer resort for London, often called London-by-the-Sea. Every week-end the place is packed with visitors.”

Dr. Charles Thrush, Kitchener Military Hospital, letter to Dunnville Chronicle, June 3, 1917.

In November 1917, Rebecca was admitted to Kitchener Hospital as a patient—suffering from terrible abdominal pain. She had acute appendicitis, but would not be operated on. It was apparent that her health was undermined by this illness, along with her previous experience with scarlet fever. All the same, she returned to active duty on the wards.Rebecca enjoyed two week-long leaves while at the Kitchener Military Hospital—once in January 1918 and again in August. In December 1918, she received a new posting (she had signed on for the duration of the war and six months after) to No. 9 Canadian General Hospital in Kinmel Park Camp, Rhyl , on the northern coast of Wales.

This was a transit camp for 17,400 Canadian soldiers waiting to be transported home now that peace had arrived.It was a miserable, cold winter. A coal strike was on, and there was little fuel to heat the hospital wards, never mind the men’s quarters. The food the men were given was terrible, and local shops grossly inflated their prices, making it difficult for the men to afford to purchase better provisions. The soldiers were anxious to return home, knowing that those who got there first would have access to the few available jobs. Tensions in the camp grew.To add to the misery, the Spanish Influenza was sweeping through Europe and North America. Kinmel Camp was not exempt from the terrible disease. The February 5, 1919, entry in the war diary for No. 9 General, reads:

“Influenza increasing rapidly in camp. Central part of hospital almost full—we have over 600 patients in hospital now. Admitted 49 yesterday and 55 today practically all influenza.“

The next day the writer reports: “Seventeen of the personnel of this unit are in hospital.” Rebecca McIntosh would join them in mid-February. She struggled for the rest of that month and into March, her breathing becoming more and more difficult. It wasn’t an ideal time to be sick—according to the hospital’s war diary, there was little coal and it was so cold that pipes had burst in the hospital and as a result, water had to be turned off in four of the wards.

As Rebecca lay in bed, another drama was playing itself out in the camp. On March 4, 1919, tensions in the camp finally boiled over and the men rioted. Local shops were looted, “loyal” troops fought with the rioters, five Canadians were killed and 28 wounded. Fifty-one Canadians faced court marshal and 27 were convicted and sentenced from 3 months to 10 years.

It’s difficult to say if Rebecca was even well enough to know of all the tumult around her. The young nurse would never return to her Nova Scotia home. On March 8, the war diary for the unit read: “Nursing Sister McIntosh of this unit died in hospital today—influenza. This sister was very popular with the unit; a true nursing sister devoted to her duty. She will be greatly missed by all.”

Rebecca was buried in St. Margaret’s Cemetery, Bodelwyddan.

Rebecca MacIntosh is commemorated on the Canadian Virtual War Memorial.

Rebecca is also commemorated on a memorial situated within the Elizabeth Garrett Women’s Hospital in London

Additional Information

Elizabeth Garrett Hospital Nuses House in Memory of foreign nurses who died in the great war.

In 1937 the Duchess of Kent laid the foundation stone for a new nurses’ home. She returned to open the Nurses’ House (the word ‘House’ had been substituted for ‘Home’) a year later. The building contained sitting rooms, common rooms and 80 bedrooms, as well as accommodation for the Preliminary Training School for nurses. The entrance hall had been designed as a memorial to overseas nurses who had lost their lives during WW1 – 39 members of the Canadian Nursing Service, 24 of the Australian Nursing Service, 15 of the New Zealand Nursing Service, 4 of the South African Nursing Service, 3 of the Colonial Nursing Service and 1 of the Indian Military Nursing Service. A plaque on the wall, bearing the arms of the Dominions, was inscribed:

“This hall and the land on which it stands were given to the Hospital to be a memorial in honour of those overseas nurses who died while serving the Allied Armies, 1914-1918.

For lamentation, memory, For pity, praise.”

The hospital has now been demolished and the whereabouts of the plaque is unknown.

There is also a memorial to all Canadian Nursing Sisters in Ottowa. The Nursing Sisters’ Memorial The Nursing Sisters’ Memorial is located in the Hall of Honour in the centre block on Parliament Hill. The sculptor was Mr. G.W. Hill, R.C.A., of Montréal. The sculptor did his work in Italy, and found a beautiful piece of marble from the Carara quarries. The completed panel was mounted in the Hall of Honour during the summer of 1926.

In the Programme of the Unveiling Ceremony of the Canadian Nurses’ Memorial, the artist interprets the sculptured panel:

The design for the sculptured panel embraces the history of the nurses of Canada from the earliest days to the First World War. The right-hand side of the bas-relief represents the contribution made by the religious sisters who came to Canada from France during l’ancien régime, and depicts a sister nursing a sick Indian child while an Iroquois warrior looks on suspiciously. To the left a group of two nursing sisters in uniform tending a wounded soldier symbolizes the courage and self-sacrifice of the Canadian nurses who served in the war. In the centre stands the draped figure of “Humanity” with outstretched arms. In her left hand she holds the caduceus, the emblem of healing; with the other hand she indicates the courage and devotion of nurses through the ages. In the background, “History” holds the book of records containing the deeds of heroism and sacrifice of Canadian nurses through almost three centuries of faithful service.

The History of Pleasant Bay.

The farms were almost all recovered from the forest, and remained ungranted for about thirty years and upwards. The first lands granted were those of Edward Timmons and of John Hingley in 1856. The largest tract of land granted was five hundred acres taken up by Henry Taylor of Margaree on the Pond river banks, in two lots — one extending inward from the seashore on the northern side, the other between McLean’s lot and that of James Mcintosh. These areas were granted for the timber they contained. They later became incorporated in the McLean and McPherson farms. McLean’s lot when granted in 1863 comprised 195 acres. The other lands granted were in lots of 100 acres.

For upwards of fifty years, the life of the community was one of hardship. Their livelihood was obtained largely from the land which they had reclaimed from the forest. Potatoes, wheat, a cereal called , “China oats” on account of the original grains having been found in a chest of tea, turnips and cabbage were grown. Their supply of meat was mostly obtained from the woods; moose were plentiful, and smaller game — partridges and rabbits. They early learned to catch the cod, but for years, the method of catching the mackerel was unknown. Lobsters were plentiful but there was no market for them. Cattle, sheep and hogs were raised. Wild fruits were plentiful in the cleared pastures and on the barrens. The maple furnished some of the sweets. The draught animals were oxen, until the arrival of the Sutherlands.

Their isolated condition, forced the early settlers to fall back upon expedients of the pioneer stage of civilization. A tallow or oil dip often served for a lamp before candles became in general use. To light the way along the rough roads on a dark night often a brand held in the hand, the other end glowing, was swung back and forth across the path. Hand wool cards, the spinning wheel and loom, were in almost every house; and the wearing apparel, bedclothes and rugs, were made in the home. Hides were tanned, dressed and made into shoes. The grain was cut with the sickle, bound by hand and set up in stooks in the field; and when in the barn was threshed by the flail. The quern or handmill for making flour was in several homes. When a grist mill was considered a necessity, the elder Trenholm’s ingenuity was brought into play. He made all the wood work easily enough. Scrap iron was found to make the shafts and spindles. There was no coal to do smith work, but he made charcoal to take its place. He quarried and made the stones, and soon the quern was supplemented by a mill on the Mingley brook which, however, produced results only when the stream was swollen.

The spiritual welfare of the people was looked after by the older men and women. Meetings for worship were held in the homes, the elders conducting the service, until a good schoolhouse was built, and in the early seventies a comfortable church. All the early settlers were Presbyterians. In the early years, church courts were held for the trial of offenders against moral or religious regulations. In those days the community was visited occasionally by a clergyman, who travelled over the mountain. The names of Mr. Shields, Mr. Kendal and Mr. Whitley are still recalled with gratitude. Although belonging to a different denomination, they were always welcomed, and they freely gave their ministrations. Mr. Whitley frequently visited the place, and coming during the mackerel season, he invariably prayed that the waters of the deep would yield its treasures to the people. Many so firmly believed in the efficacy of his prayer that they welcomed his coming even on that account. Mr. Gunn of Broad Cove was for a time a yearly visitor and performed the rites of marriage and baptism. His visits were looked forward to with pleasure and his stay, though brief, was a note worthy event.

There has been no settled clergyman in the community except for a short time when the late Donald Sutherland of Earltown lived in the settlement. Always, however, the people met on Sunday and had a service consisting of song, prayer,and the reading of a sermon. Alexander Mcintosh, a son of John, for long read the sermon and led in the singing. Previous to May, 1895 Pleasant Bay was included in the Cape North of Aspy Bay congregation. Since that time it has been under the care of the Presbytery of Inverness as a Home Mission station. This Presbytery is generally able to provide the people with a student catechist during four or five months in the summer time.”

The education of their children was a thing desired by these people. In their home what instruction could be given was earnestly done. The first school teacher was one John McKay from Margaree, who taught in a log school house. A barn, or an old house, was some times the improvised school. Ewen Mcintosh, a son of young Donald was the next teacher, who was himself for sometime under the tutelage of the Rev. Donald Sutherland. North East Margaree supplied teachers to the settlement for a number of years. After that for some years, a local supply was available. The result has been that from this isolated locality men and women have gone out into the world as school teachers, trained nurses, academy and college students, men of business, and school and college instructors. Some of their names appear on the graduate lists of Dalhousie, McGill and Harvard. Among the members of the class of 1915 at Dalhousie College, John P. McLean a great grandson of pioneer John, stood high both as a student and an athlete. He was the president of his class, and the winner of the McKenzie bursary, but he died during his sophomore year. A brilliant young minister, John P. Mcintosh, was a grandson of the early settler James. His course at Dalhousie was marked by ability in debate, and in the histrionic art. At Pine Hill Theological College he was easily a leader. After a successful pastorate at Onslow, he was settled in the congregation of Bridgewater, and had a George S. Campbell Travelling Scholarship from Pine Hill at his disposal. He was looked upon as a coming man in the councils of the church, but he fell a victim to influenza and died at Bridgewater, in 1918. Another grandson of James is at present a missionary in Trinidad, and a grand-daughter graces the manse in far away Korea.

Farming is the mainstay of Pleasant Bay, but an important money product is the fisheries. In the early times boating fish and products of the farm to Cheticamp, and bringing back in exchange things they could not produce at home, was a tremendous drudgery. It, however developed such expert boatsmen that during the whole period that Cheticamp was their market there was never a serious accident. In 1887, John Forrest of Antigonish established a lobster cannery at the mouth of the brook of the John Mcintosh lot. A general store was opened in connection with the cannery, and this reduced the hard labor. This business passed into the hands of W. H. McKenzie and then of Harlon Fulton of Halifax. Meantime a small Government wharf was built. In 1901, H. H. Banks of Halifax succeeded Fulton in the business. The betterment of the community was to Mr. Banks of more importance than profits from the business. When motor boats were yet on trial, he introduced them to the settlement, and installed a gasolene engine for hauling up boats. In fact, he was seldom happier than when making plans for improvement. Shortly before his death, Mr. Banks changed the business into that of a limited company. Later, Mr. George S. Lee of Halifax acquired a controlling interest, and is the present general manager with headquarters at Halifax. A. H. Mcintosh, a grandson of John, who had been connected with the business from its inception, continues to be manager at Pleasant Bay. The lobster and salmon fisheries continue good, but the mackerel fishery has of late years been rather uncertain.

During the great war, Johnnie Mcintosh, a grandson of Donaldson, although but a lad of sixteen, being large and mature for his years managed to enlist. He reached England but during his course in training, died in hospital. Rebecca, a sister of the Rev. John P. Mcintosh, went overseas as a nursing sister, but died in Wales when apparently convalescent from sickness and when about to return home. Two great grandsons of the early Andrew Moore, saw active service, and were both gassed and wounded on the firing-line. A great grandson of John and grandson of Squire Mcintosh joined the Royal Flying Corps and received his commission. The cessation of hostilities prevented him from getting overseas. Another grandson of the Squire saw active service in a construction corps. A grandson of Ned Timmons, and a great grandson of Moore were in training overseas at the time of the armistice. A great grandson of John McLean spent many months in hospital from diseases contracted during the severe training for active service.

James McIntosh Rebecca’s Grandfather pioneer settler

In the meantime, James Mcintosh, who had been living in Baye St. Lawrence, had returned to Grantosh and begun to make a home for himself and family on the wooded intervale of the Pond River about two miles from the seashore. He had a good companion and helper at his hard task, in his wife, Annie Campbell. Later there were five sturdy sons and three daughters to aid in the work.

James had a fair education in the Gaelic language, and after a regular religious service was established in the community, he was the leader in that language.