Griffith Edwin Rhys Thomas was born in Dyserth in 1896. His parents were originally from South Wales – his father, Joseph Thomas, from Aberdare and his mother, Margaretta Letitia from the village of Clydach in the Swansea valley. They were both certified teachers and from 1892 to 1914 Joseph Thomas was the headmaster of Dyserth school.

His early life was blighted by tragedy. In 1878 he married a fellow schoolteacher, Elizabeth Ann Davies ( Bessie). Sadly she died on the 16th of January 1880 after giving birth to their son Percival Wilfred. She was 25 years old.

So…by the time he was 32 Joseph Thomas was a widower. The 1881 census shows him lodging in Hill House, Dyffryn Clydach with a ‘Thomas’ family. Could they have been relatives? His baby son was living with Bessie’s widowed mother, Phanuel Davies, in Sketty, Swansea. She too was a schoolmistress. At the same time his future wife, Margarette, lived in Fynne Street, Swansea with her newly widowed mother and her siblings Edwin, Agnes, Adelina and 10 month old Griffith – all of whom had been born in Clydach. 16 year old Margarette was a pupil teacher. Education ran in the family as her father, Griffith Thomas, had been an Inspector of Schools..

We don’t know the circumstances by which Joseph met Margarette. Perhaps the fact they were both teachers had something to do with it. They were married in London in St Saviour’s, Denmark Park, Camberwell on the 23rd of December 1890. Joseph was now the schoolmaster at Shocklach school near Malpas. He took his young bride back to Shocklach where in 1892 their first child – Arthur – was born. Percival, who was living with them, now had a brother.

Not long after this they moved to Dyserth where Joseph had been appointed headmaster of the school. As we know, Griffith (known as Edwin) was born in 1896, followed two years later by brother Hugh. The family lived in Tan y Bryn House in Dyserth village. The Dyserth school log book gives a revealing picture of how schools functioned at the time. It would seem that, despite having babies and looking after her family, Margarette worked in the school alongside her husband throughout their time in Dyserth. Their own boys were amongst their pupils.

The headmaster’s entry in the logbook after the summer holidays of 1914 states:

“On the second of August the Great War commenced, the scholars returned to school full of military enthusiasm.”

In December 1914 Mr and Mrs Thomas retired. The following appears in the school log book:

“December 8th

Visit without notice

It has always been a great pleasure to visit this school, which has been conducted by Mr and Mrs Thomas with indomitable energy, incontestable efficiency and whole-hearted devotion for over twenty years. I desire to express my deep appreciation of the excellent services they have rendered in the cause of education in this neighbourhood and I wish them peace and prosperity in their retirement.

R Rhydderch (SubInspector of Schools)”

The Thomas’s had clearly involved themselves in all aspects of village life. Mr Thomas had been the organist and choirmaster in the church throughout his time in Dyserth. The Rhyl Journal of the 3rd of January 1914 carries a lengthy account of the village’s farewell celebrations. Many people attended including local dignitaries and former pupils. The paper records that “presentations were made in the schoolroom amid prolonged cheering and singing of ‘for he’s a jolly good fellow’. Mr Thomas’ speech in response included these words: “if he dared to give the people of Dyserth a message it would be this; that they should live for their children for without doubt their children were the greatest heritage God had given to man”

The couple said that although they were retiring to London they would continue working. By now Edwin would have been 18 and was, it would seem, a civil servant. We do not know the time frame for sure, however it was probably at the outset of war that he enlisted at St Paul’s Churchyard and joined the 15th (County of London) Battalion (P.W.O. Civil Service Rifles) which was part of the London Regiment.

Before the Great War the London Regiment had raised 26 battalions many of them made up of men who shared a common occupation. The 15th Battalion was made up of civil servants who lived and worked in London. Its headquarters were at Somerset House. The Battalion was mobilised in August 1914 and, in March 1915, went to France. In May it became part of the 47th (2nd London) Division and later that year fought in the Battle of Loos.

The Battle of High Wood in which Edwin Thomas was killed was the culmination of a series of attempts by the Allies over the preceding months to capture the wood which was of great strategic importance. It was the last of the major woods to be taken by the British during the Battle of the Somme. The wood itself is not large. However, because of the immense human carnage which took place between July and September 1916 the remains of many thousands of soldiers remain there to this day. Edwin’s remains may possibly lie there too.

This account of the capture of High Wood on the 15th of September 1916 is taken from www.ww1battlefields.co.uk

“The attack on the wider front was preceded by a three day artillery bombardment, but at High Wood the opposing front lines were considered too close together for this to be done. Four tanks were to lead the infantry advance at High Wood, and the principal attacking force was to be the 47th (London) Division, part of III Corps. On their right were the New Zealand Division, and on their left the 50th Division.

The 47th had only recently come down to the Somme and were commanded by Major-General Charles Barter. They relieved the 1st Division in front of High Wood on the 10th of September.

Barter and his brigade commanders were unhappy with the plan of attack proposed, and wanted to change it. They felt (and proved to be right) that tanks would not be able to operate in the mass of tree stumps and craters that High Wood had become, and they also wanted to withdraw their troops temporarily from the front line to allow a bombardment of the German positions before the attack. However III Corps Headquarters refused these changes, and so Barter had to go ahead with the original plan.

All four tanks to be used at High Wood had problems, and were late in getting to their start points for the attack. Because of their slow speed, they needed to be well ahead of the infantry to be effective, but in the event when the infantry advanced at 6.20 a.m., they soon left the tanks behind. None of the four tanks made great progress, although in one case their gun did harass the enemy. Two tanks ditched, one was set on fire and the last (Clan Ruthven) got stuck on a tree stump. A success elsewhere, the tanks were not able at that stage to deal with land as damaged as that in High Wood.

The infantry attack on the wood was made by the London Irish (18th Londons), Poplar & Stepney Rifles (17th Londons) and two companies of the 15th Londons (Civil Service Rifles). They suffered from enemy machine-gun fire as, just before zero, they lay in No Mans Land ahead of their trenches. The German artillery also opened up. After the assault commenced, 80% of the Civil Service Rifles became casualties, with two Company Commanders killed, Captains Arthur Roberts and Leslie Davies. Roberts had crawled close to the German trenches and was shot dead as he gave the order to charge. His body was found only after the War and he is now buried in Cerisy-Gailly French National Cemetery south-west of Albert.

The survivors from the London troops got back to their trenches, and two more battalions, the 19th and 20th Londons were sent up in support.

On the left of High Wood, troops trying to advance were caught by machine gun fire from the west of High Wood. The 7th Londons on the right, however, advanced to and took the Switch Line.

In the Wood, the Post Office Rifles (8th Londons) followed up the attack of their fellow Londoners, and suffered losses from withering machine gun fire. They did however manage to reach the German trenches. The 6th Londons followed on at 8.20 a.m.

By mid-morning there were five battalions desperately fighting for possession of High Wood, and they called for an artillery barrage on the west and north-west part of the wood, and trench mortars to bombard the eastern portion. The Civil Service Rifles attacked once more after this, and the Germans started to surrender.

By 1 p.m. on the 15th of September, the British finally held High Wood, and it had been taken, after all the attempts described above, by the 47th (London) Division. But success came at a price. The Poplar & Stepney Rifles (17th Londons) suffered 332 casualties, and the other battalions involved had suffered serious losses as well.

On the 19th of September, the 47th Division which had lost more than 4,500 men was relieved by the 1st Division. At an hours notice, Major-General Barter, commanding the 47th Division, was dismissed by the III Corps Commander, Pulteney, for wastage of men.

Barter protested his innocence; after all he had wanted to withdraw and bombard the wood, but this had been refused. After losses had been suffered, a bombardment had finally been sanctioned, and the wood was then taken. Although there was never an official inquiry, Charles Barter was later knighted.”

By a bitter twist of fate retirement for the Thomas’s had not brought happiness. Edwin’s death must have caused them great pain. There is very little documentation regarding Edwin’s life in the army. However the Register of Soldier’s Effects shows the outstanding payments – wages and gratuity – sent to his father after his death. One can’t help but think ‘what price a life?’

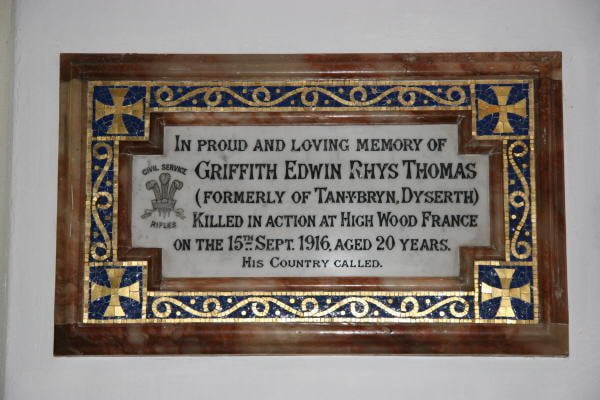

Edwin is commemorated in St Bridget’s Church, Dyserth as well as the Thiepval Memorial in France. Joseph died in 1920. Margarette went back to Dinas Powis in South Wales. Percival died in Vancouver in 1954.

In one way or another the Thomas family had left their mark in Dyserth.