Charles Victor Roberts was born in St Asaph in 1888 into a Welsh speaking family. According to the 1891 census his father, Joseph (an agricultural labourer) and his wife Ellen were living in Cornel, a row of cottages in St Asaph between Glan Elwy and Ty Cerrig. Their children, Charles and Jemima Ann (Minnie) were 3 and 2 years of age respectively. Sisters Alice, Eleanor Mary (Nell) and Ann came later. Nell’s grand-daughter, Vina Johnston, has kindly contributed to the story of her great uncle Charlie.

It is difficult to piece together what exactly happened to the family. Vina knows that the mother left them at some point but is unclear as to when. Whatever, the 1901 census states that thirteen year old Charlie was a domestic servant in the County School in St Asaph. His father was boarding in Beaumaris on Anglesey and employed as a driver with the Royal Artillary / Royal Engineers Militia. Tragically the girls; Minnie(12), Alice Maud(8), Nell (7) and Annie (6) were inmates in the St Asaph workhouse which, as it happens, was next door to the County School. There is some evidence that in 1906 – the year when Charlie joined the army – the family was living in the Blue Lion, Cwm. Vina remembers her mother Gwen saying that Nell was 11 years old when her mother left them and that she went to live in Liverpool. Despite this she kept in touch with the family, particularly Annie who eventually also lived in Liverpool.

Ten years later in 1911 the children’s circumstances had changed. Charlie was in the Army, Alice was boarding in Gamlin Street, Rhyl whilst working as a waitress in a hotel. Nellie was employed as a maid / domestic servant in a big house in Rhyl – The Poplars, and Annie was a domestic servant in Pen y Bryn Farm, Dyserth. (the home of Robert and Thomas Evans whose names are also on the Dyserth Memorial). Subsequently all four girls married and had families of their own. Nell’s husband was made head gardener at Bodrhyddan which entitled them to a home on the estate. Thus newly married in 1913 they were living The Lodge. Alice sadly lost her first husband in the First World War followed by her son in WW2.

But what of Charles? Many of his service records are online and give a great deal of detail regarding his life in the army. In view of what had happened to his family it is not surprising that Charles became a soldier. Perhaps he was following in his father’s footsteps, perhaps the lure of security, accommodation and wages attracted him or maybe it was the promise of adventure. Whatever the reason, he tried to enlist in the Militia on the 24th of January 1905. He gave his age as 18 years and 1 month. He was 5 foot 2 inches tall with a fresh complexion, hazel eyes, brown hair and a heart, cross and line tattoo bearing his initials on his left forearm. Unfortunately he was rejected because he was too short!

A year later in March 1906 he successfully enlisted at Wrexham into the regular army. He was 19 years and 3 months old, a general labourer living in lodgings and applying to join the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. He didn’t settle very well at first. On the 6th of June he was “absent from pass from 12 noon until apprehended by the Civil Power at St Asaph on the 14th June” He attempted to ‘escape’ again three days later.

Vina wonders why he changed his mind. Did it coincide with his mother leaving? Was he missing his sisters or was he just a free spirit who had not been used to discipline?

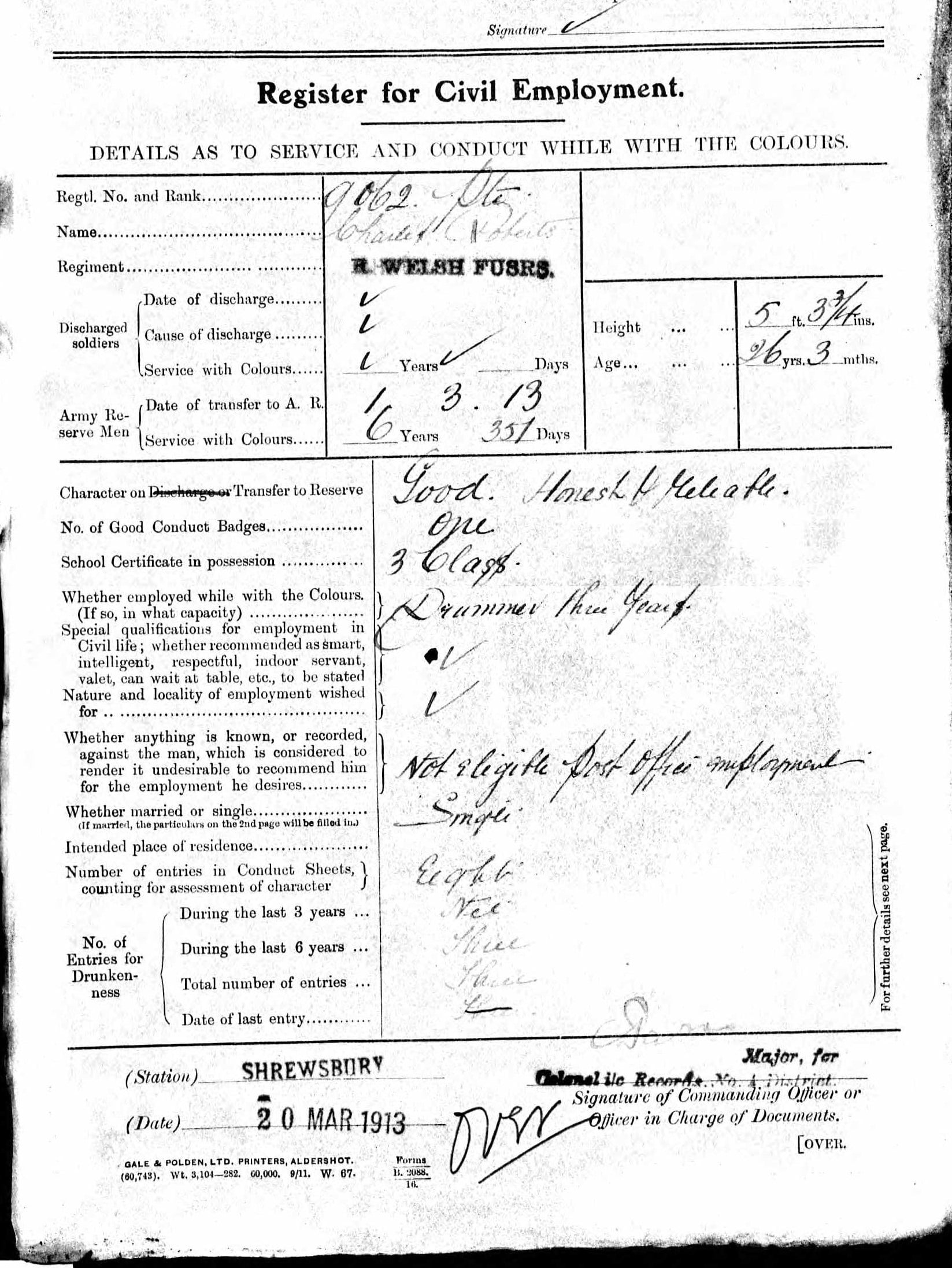

His medical examination after 6 months service showed a gain in height to 5 foot 3 inches and a gain in weight from 113 to 122 lbs. He was pronounced fit to serve. After almost a year in the UK he served six years overseas in India and Burma finally coming home in March 1913. The conditions of service required him to be transferred to the Reserve. He enrolled in Section A, 1st Class Army Reserve and was released on the termination of his engagement in March 1914. For much of the time in the Army he had been a drummer.

Major Paul Phillips(retired) has kindly looked through Charles’ records and summarised his army life:

“I should explain that in those days where few wore watches and the curse of the mobile phone was a distant nightmare, soldiers were guided by either bugle calls or drumming. Meal times, parades duties, moving in formation and so on all had their own tunes or rhythms which all ranks were familiar with. Last Post, (basically lights out) and Reveille, (get out of bed) are calls that you may be familiar with. Different regiments favoured either the drum or the bugle but at that time I should think many used both means of communication.

The regiment depended totally on these guys to ensure that soldiers were in the right place at the right time. Drummers usually carried a bugle as well as a drum and could make the calls on either instrument.

You will notice that on the 28th of August 1909, while serving in Burma he was charged with “being absent from the tattoo”. Drummer Roberts had bunked off to break into the family hospital! In the process he had failed to pass on an order using his drum, no doubt causing chaos as the troops would not know where to go and what to do. It is difficult to read the conduct document but I would imagine 3 days in the cells was quite likely at that time (and in mine for that matter although we rarely used bugle or drum calls as the telephone was more effective and quieter). The previous year he had earned himself 3 days confined to barracks for failing to “sound the dress” A drum or bugle call that tells the soldiers to parade, perhaps for inspection or dismissal at the end of the day.

Drummer Roberts served mostly in the Far East in Burma and in India. He was hospitalised twice in Burma; once for malaria and once for what I interpreted as a boil. These of course were very common and very unpleasant in the tropics in those days before antibiotics.

You know already that Drummer Roberts got off to a shaky start after a couple of months service when he disappeared for 10 days for which he was awarded a relatively mild sentence of 10 days confined to barracks. In the middle of this he disappeared again and got himself a week in the cells which would have been accompanied by lots of unpleasant chores (as would being confined to barracks. Fatigues such as peeling potatoes for six hundred hungry men, were commonplace!!)

Drummer Roberts was often drunk, (and so would I have been in Burma in the 1907s) and he was occasionally in trouble associated with that condition. Causing a disturbance in a brothel was one that got him ten days in the cells.

You will, perhaps, be surprised that Drummer Roberts was discharged with a conduct of ‘Good’ in spite of a good number of brushes with authority. The Army did not and still doesn’t, I suspect, count offences committed more than six years ago when assessing conduct. Drummer Roberts had a clean sheet for three years and had committed three offences in the previous three years. The five offences prior to that are not considered although they still appear on his records. One less offence and, today, his conduct at discharge would be classified as “Exemplary”!

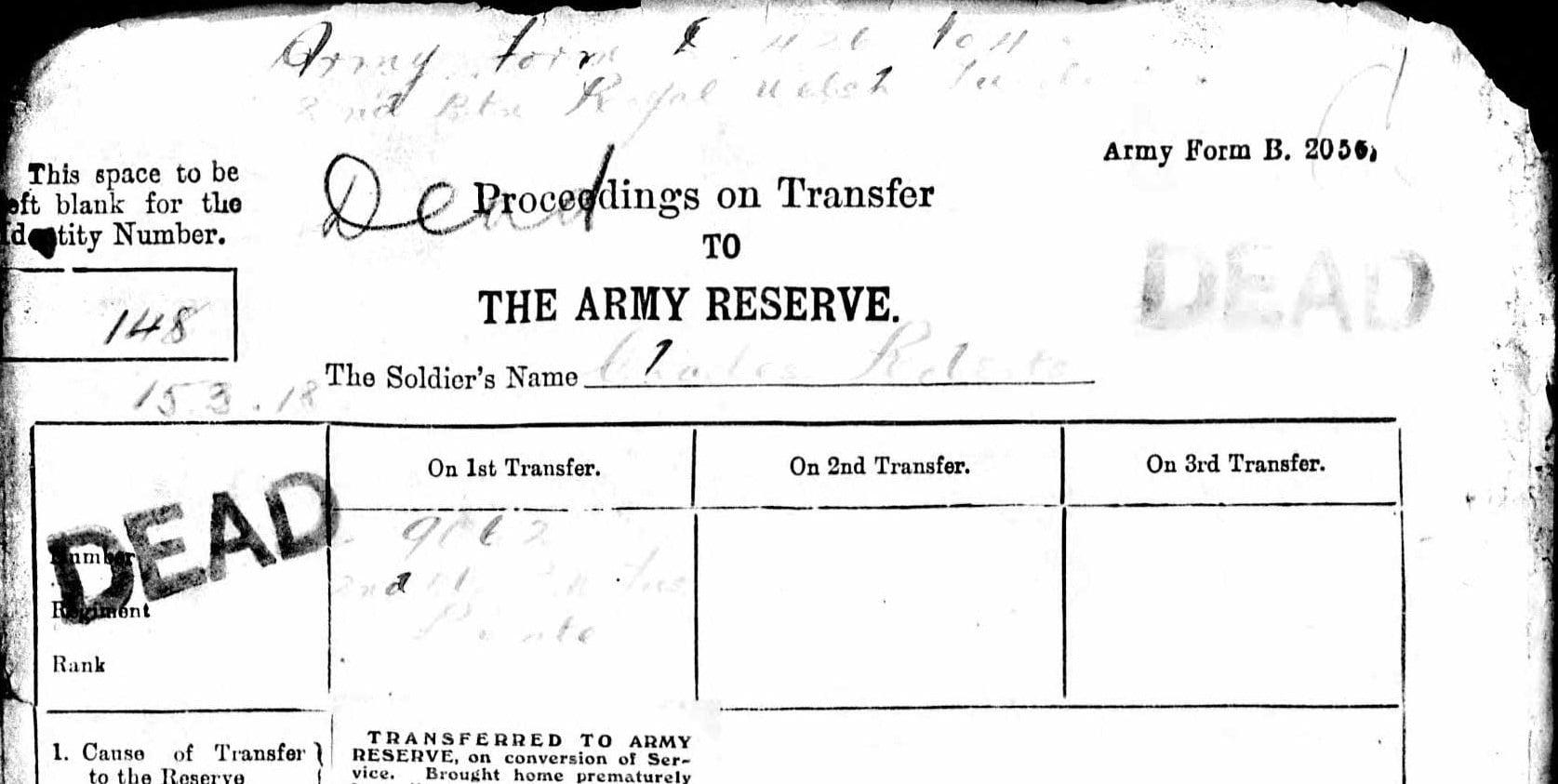

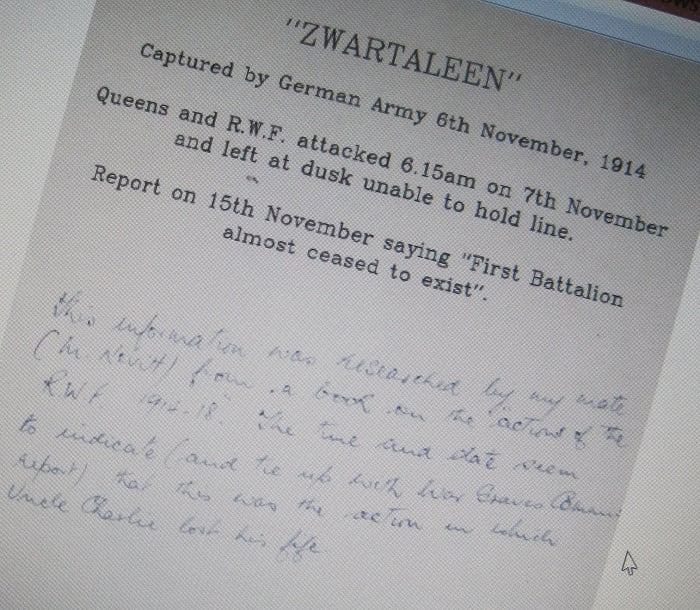

Poor man. He enjoyed barely a year as a civilian before the war broke out and he was killed two months later perhaps during the First Battle for Ypres, The Battle of Polygon Wood took place at the estimated time of his death between 28 and 31st October 1914 although I was unable to establish whether the Royal Welsh Fusiliers were involved.”

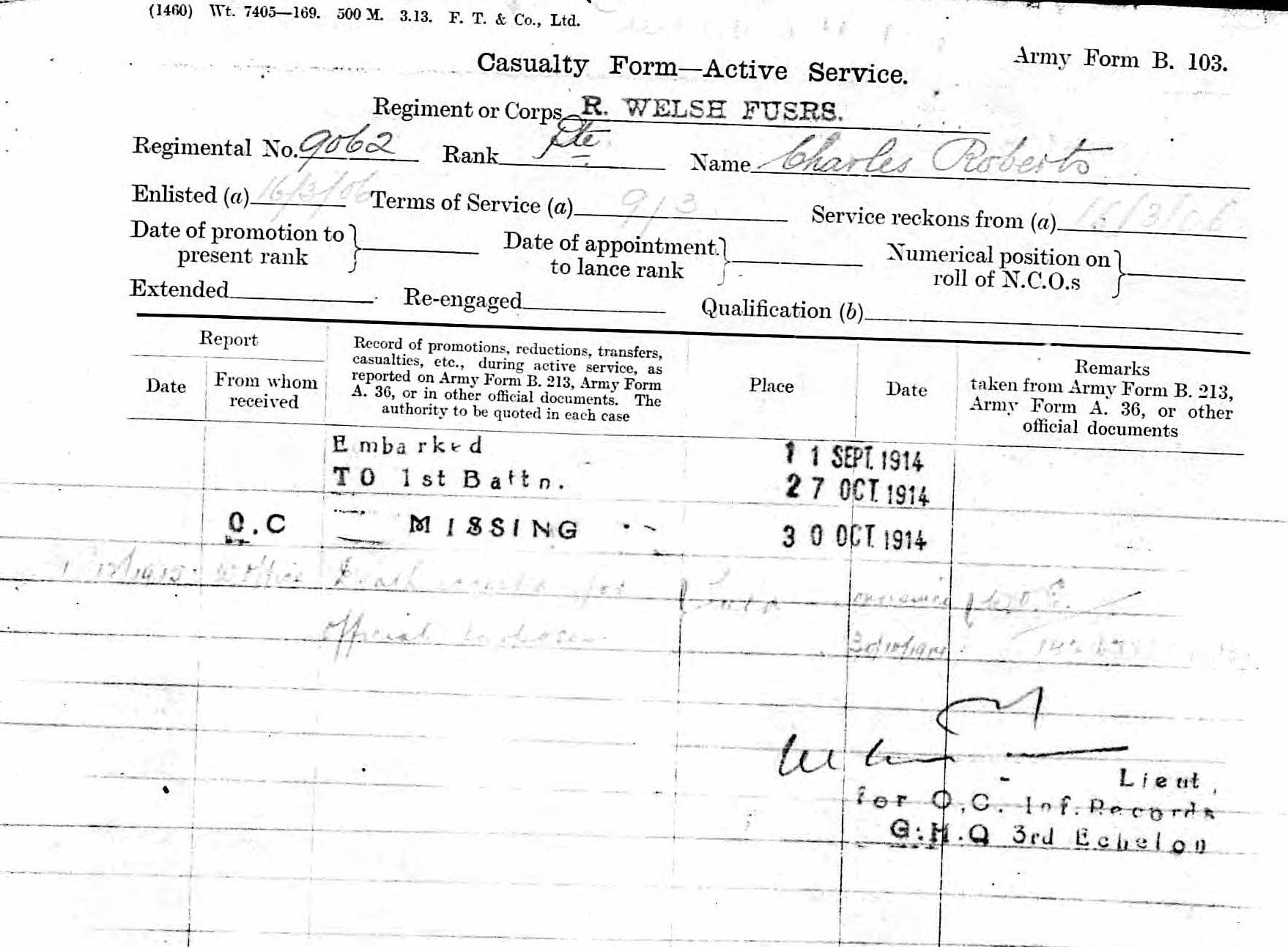

So we see that at the outbreak of war Charles was called up. Vina says “I remember Mam said that her mother (Nell) stood by The Lodge gate and watched him go down the road towards Rhuddlan – presumably to the railway station. She told me she had felt an awful feeling of foreboding that she wouldn’t see him again.” She was right. The Casualty Form shows that Charlie embarked for France on the 11th of September 1914, joined the 1st Battalion on the 27th of October and by the 30th of October was declared “missing”. He had been back in the Army for just 50 days. His body was never found.

Family members have tried to find out what happened to him.

Charles is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres. Minnie, Nell and Annie each named their sons after him.

As Vina says “He must have been much loved”

The 1914 Star (colloquially known as the Mons Star) was a British Empire campaign medal for service in World War 1.The majority of recipients were officers and men of the pre-war British army, specifically the British Expeditionary Force (the Old Contemptibles), who landed in France soon after the outbreak of the War and who took part in the Retreat from Mons (hence the nickname ‘Mons Star’). 365,622 were awarded in total. Recipients of this medal also received the British War Medal and Victory Medal. These three medals were sometimes irreverently referred to as Pip, Squeak and Wilfred.

The Clasp, often referred to as Clasp and Roses was instituted in 1919 and awarded to those who had operated within range of enemy mobile artillery during the period from the 5th of August to the 22nd of November 1914. When the ribbon bar was worn alone, recipients of the clasp to the medal wore a small silver rosette on the ribbon bar. (Wikipedia)